NYC MTA versus HK MTR

Battle of the business models in urban transport

As a native New Yorker I admit I have an affinity for other formerly British colonial financial hubs that wish they were city-states and not attached to the major countries currently rolling back all their civil liberties (and also grow high-rises like a bumper crop), but as a New York chauvinist it chagrins me to admit that I really like aspects of Hong Kong’s urban design that I find superior to that of New York City. First and foremost among them the Hong Kong subway MTR.

So, the questions are,

In what ways are the HK MTR better than the NY MTA/NYCT?

Why?

Well, many answers of the first question become evident simply from user experience. The MTR’s stations are clean and air-conditioned, have many retail businesses on the concourse, and have wide station platforms, universal platform doors and universal platform elevators - NYCT has ADA capability in only 24% of its stations. Their system has wi-fi services - even in the tunnels! Their rolling stock is new and has universal open gangways, and they have an on-time performance of over 99% - NYCT reported a mere 71% on-time performance during the last ‘normal’ year of 2019. The MTR’s service has short headways of around two minutes between trains during rush hours - a feat NYCT also matches but only due to interlining, where multiple services run the same routes or tracks.

The MTR’s fares are relatively cheap compared to NYCT, as distance based fares start at ~50 cents USD and max out at ~$6.50 USD, though the top fares are usually reserved for trips that bring you to Disneyland or the HK airport off Lantau Island. By comparison, one trip on JFK’s AirTrain costs a whopping $8.25, on top of the normal fare and, unlike the MTR’s Airport Express, isn’t a one-seat express ride to central Hong Kong. NYC used to have an Airport super-express that took the A train’s tracks to JFK from a special platform in Times Square, but that still dropped you on the far end of long-term parking and required a further bus ride, and also was discontinued in 1990.

The MTR also has the best integrated pre-paid smartcard of any system, the Octopus Card, which can be used not only in the subway, trams and buses, but also taxis and most retail and food establishments, supplanting most everyday debit card uses.

Of course, there are still ways in which the MTA holds on by comparison. NYCT is still one of the only 24/7/365 subways in the world, and the whole system has one flat fare of $2.75 USD, with every ride after the twelfth in any given week being free thanks to OMNY. Overall this makes NYC more expensive than HK, but far cheaper than, say, London’s Underground. NYC still has the most stations in the world at 472 (or 424 if you merge transfer stations) to Hong Kong’s 98, and NYC has 400km of route miles to Hong Kong’s 271km, with many of those routes having three or four tracks for express service, a feature unique to NYC.

Basically, a Hong Konger would find New York’s subways extensive but smelly, confusing and dirty, while a New Yorker would find Hong Kong’s subways bright and clean, but wonders where they all went when he’s drunk in the middle of the night and wants to go home.

So, why is this? Most of that appears to boil down to budget.

Many of the things mentioned are simply because NYC’s system is older (narrower platforms that make platform doors or station elevators impossible, older rolling stock and the sheer number of stations/tracks to upgrade for improved service, etc) but many of those problems can be solved with money and, despite NYC being the richest city on earth, with a larger economic output than the entire country of Russia, the NY MTA is a starved beast for operations budget that also, incongruously, happens to have the most expensive capital budget in the world by an order of magnitude, precluding most projects from getting off the ground (RIP 2nd Ave Subway). Meanwhile the Hong Kong MTR turned a profit during the height of the Covid pandemic and is constantly growing.

In my opinion, Hong Kong simply has the better budget and business model.

As I see it, there are two basic models to fund metropolitan transit systems, which I will call the European model and the Asian model. The European model presupposes transit as a public service, and as such does not expect it to turn a profit. They budget their metros through taxes, and their farebox recovery ratios - that is, the percentage of the operating budget covered by collecting fares - is often very low. Paris’s Metro has a recovery ratio of 29%, Rome hovers around 36%. However, relieved of the requirement to make money, the systems can spread organically and without stop, meaning that institutional knowledge can better be retained and developed in-house. When it comes to capital construction, doing things in-house costs one whole hell of a lot less than retaining contractors, but in order to be cost-effective, in-house expertise needs to be used more or less constantly, which can’t be done if you aren’t building constantly.

The Asian model expects transit to make a profit, but ironically not from transit. The Tokyo Metro and the Hong Kong MTR are exemplars of this, in that they are real estate development firms first and foremost, and transit companies second: As public corporations, the transit companies secure exclusive rights of way from the government to develop train lines, but the lines are mostly just there to increase real estate value, which is then captured by the transit companies in the form of rent. The transit companies then take this rent and invest in more lines and more property development.

Meanwhile, the American model, if there is one, takes the worst effects of both these models: The American model presupposes profitability but doesn’t allow public corporations to invest in real estate. Furthermore, despite being corporations they can’t set their own fares, which means fares are set artificially low. New York used to have multiple private subway companies - the Interborough Rapid Transit system and the Brooklyn Rapid Transit system which became the Brooklyn Manhattan Transit system, and the Independent Subway - but the state got to set the fares, which were kept at 5 cents for 44 years, and have consistently lagged behind running costs. The consequences of this was the consolidation of all three systems under public ownership when their operating companies went bankrupt, the reduction of service and the elimination of many lines due to inability to maintain the system.

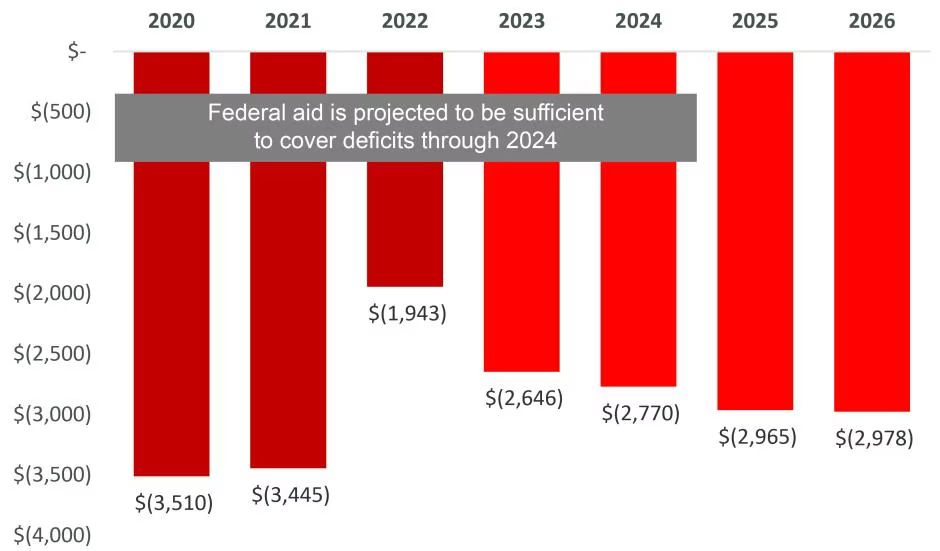

Coupled with federal defunding of transit and the city almost going broke in the 1970s meant that capital development basically stopped, service suffered and the system had to work a maintenance backlog for over 25 years. To this day, a significant portion of the MTA budget is simple debt management accrued from what us New Yorkers like to call the Bad Old Days™, and the woes of the system were exacerbated by Covid to the point that the subway runs a massive deficit and only continues to operate due to pandemic-related federal bailouts.

By comparison, the MTR turned a profit during the heights of the Covid pandemic in 2020, even as their transit operations operated as a loss, because their money largely came from rents - of the properties around the stations, and of the shops within the stations. The MTR continues to be one of the most profitable transit companies worldwide and the sixth largest developer in Hong Kong.

These all have political reasons and downstream knock-on effects. The latter turns everything into a force multiplier. NYCT is starved for cash so maintenance gets deferred or paid for with bonds, which hurts service levels and increases the percentage of the budget that doesn’t actually go towards service or improvements, as those debts have to be serviced. NYCT historically can’t develop on any schedule, so they can’t keep in-house engineers and planners who are capable of such work, and they can’t rely on local businesses to provide rolling stock because the orders are so infrequent, so there are simply no local businesses that provide parts or products. This means NYCT is overly reliant on outside contractors, which bloats budgets every time a capital improvement project is proposed. To build a mile of subway in NYC is eight times more expensive than the next most expensive city, not just because we have all these tall buildings in the way and hard granite to blast through, but also because we forgot how to build subways.

Meanwhile the MTR, as de facto developer of a significant swath of urban Hong Kong, can functionally print its own ridership, since it can simply develop homes and businesses on top of new stations at the density that would support high transit ridership. It helps that Hong Kong has some of the most hostile geography for urban sprawl and the lowest car ownership rate of any first-rate city, but the freedom of the corporation to naturally develop transit-oriented development helps accentuate such in a virtuous cycle, and because it turns a profit the system remains appealing to commuters and budget-neutral for taxes.

As for the politics, well, that’s a whole other can of worms and this blog is going on long enough. Suffice it to say, however, that different models produce drastically different results.

Another thing to talk about is the over-dependence on subway transit that NYC has; a lot of the city's transit problems (particularly the transit deserts in Queens and the Bronx) could be solved if instead of building subway lines all of the time, light rail could be built instead (in particular for Queens, the Bronx, and one area of Brooklyn (a YouTuber who comments on public transit in New York City has made a case for building light rail instead of subway all of the time: https://youtu.be/J6YoMY-z8SA?si=rMkdGVeMZKqXN79J